Newborn Care

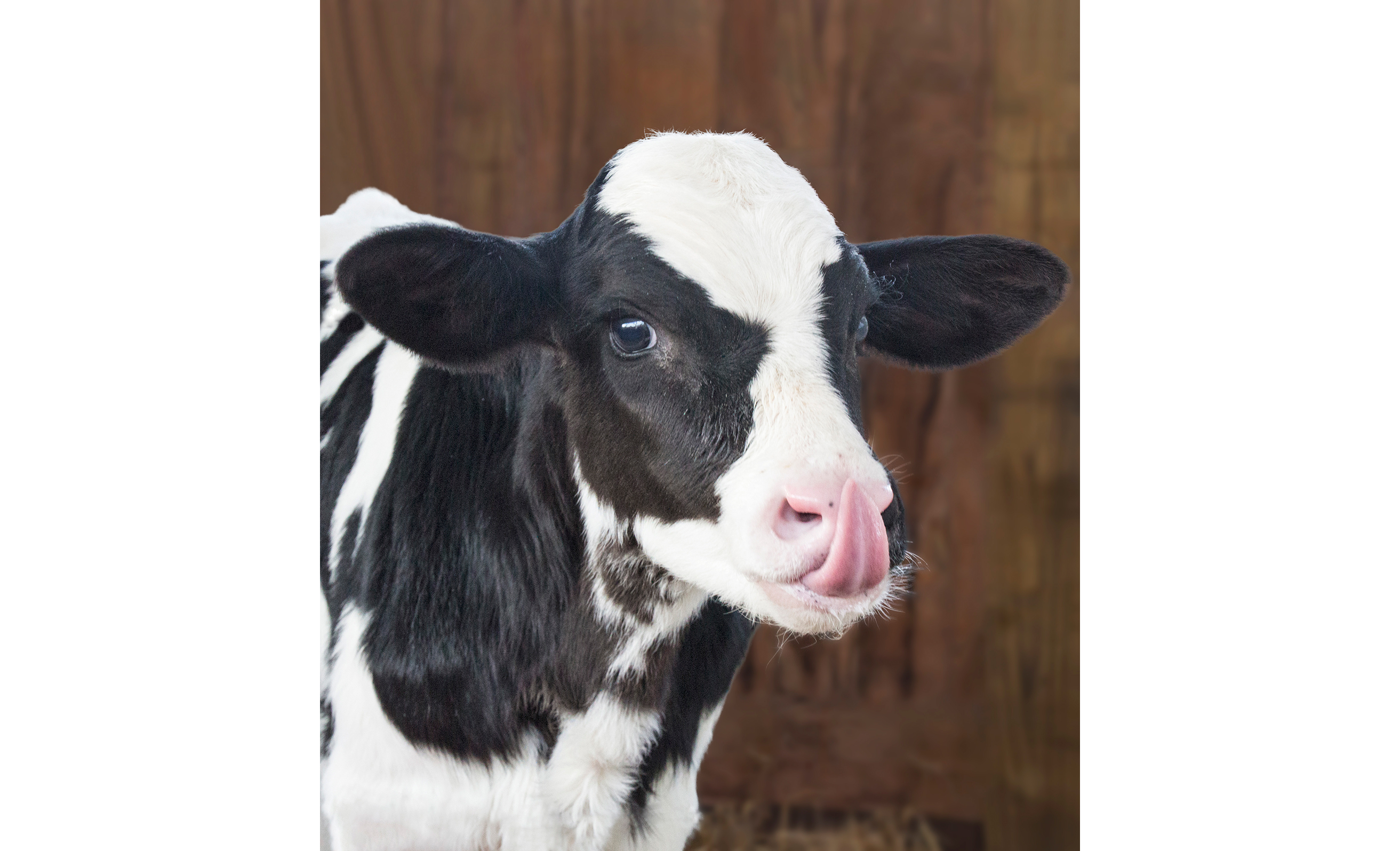

Lima Bean at two days old.

Baby calves, like human babies, have immature immune systems. Since the Nottermanns’ calves come from different dairy farms, each one is vulnerable to different germs. Until the calves’ immune systems get stronger, the Nottermanns are very careful! Each calf has his own pen, bottle, and water bucket. Before anyone can enter a calf’s pen, they must first step into a bucket of rinse water to clean their boots and then into a bucket of sanitizing liquid.

To avoid spreading disease between farms, every person puts plastic booties over their shoes.

Lima Bean and the other calves are bottle-fed in the morning and again in the evening for the first two weeks. As a newborn, Lima Bean gets two quarts (which is eight cups) of milk twice a day. As he grows bigger, this will increase to three quarts (twelve cups) twice a day.

Helm carefully weighs out the powdered calf-milk formula for each calf and mixes it with warm water (110° F).

The temperature of each bottle is checked with a long thermometer.

Lima Bean’s first task is to learn how to drink from a bottle. Most babies catch on right away, but some struggle. To make sure the milk goes into his stomach and not down his windpipe, the person feeding Lima Bean holds the bottle above his head so that his head tilts up. The first few times Lima Bean is fed, someone (in this case, the author) is in the pen with him to hold his head in the right position. He quickly gets the idea that he can get food from a bottle, and he gets ready to grab the nipple as soon as he sees it coming. After he demonstrates that he can drink an entire bottle of milk with no one holding his head, he is introduced to the “autopilot.”

The autopilot is a contraption that hangs over the edge of the pen to hold the bottle in the correct position. The first time Lima Bean tries the autopilot, he gets confused about what to do with his tongue. He sticks it sideways out of his mouth rather than curling it around the nipple.

Many calves do this in the beginning. Nancy and Helm just laugh and call this “stupid tongue,” knowing that the calves will quickly figure out how to drink correctly.

As Nancy moves through the barn, she feels all the calves’ ears. Cold or droopy ears tell Nancy that a calf is not feeling well. Happy calves twitch their tails from side to side when they are drinking. Just like human babies, calves are delicate and get sick easily when they are first born. To help build their immune systems and keep them healthy, Nancy mixes up Chinese herbs and feeds them to the calves with a syringe. The calves also get a vaccine squirted up their nose to prevent respiratory diseases. This feels tickly, but they don’t seem to mind.

Nancy checks on the calves several times a day, because she finds it easier to catch and treat an illness early on, before the animals get very sick. If Nancy is concerned about a calf, she’ll take his temperature using a people thermometer. You are probably familiar with having your temperature taken, either under your tongue or in your ear. However, inserting the thermometer in the anus (where poop comes out) gives the most accurate readings, so this technique is used for animals and human babies. Normal body temperature for a calf is 101.5°F, which is 2.9 degrees warmer than for the average human.

Nancy is always checking out the calves' poop, also known as manure. She can tell if a calf is healthy by looking at his poop. “Perfect poop” is semi-solid, with a nice brown color and not too runny. Loose, yellow, white, gray, or extra-smelly poop is a sign that something is wrong. Newborn calves' bodies are 70 percent water, so if they start losing a lot of body fluids through diarrhea, they get sick quickly. Diarrhea in calves is called "scours" and can be serious if not treated immediately.

Just like with people, a calf with diarrhea needs extra fluids so they don’t become dehydrated. So, in addition to Chinese herbs, Nancy treats diarrhea with supplemental fluids under the skin in a way that's similar to a human receiving intravenous (IV) fluids. She positions a needle under the calf’s skin and holds or hangs the bag over the calf’s back so that the fluid flows down the tube, through the needle, and into the calf simply by the force of gravity. Here she is letting the calf suck on her fingers to comfort him and to encourage him to stay still.

Lima Bean weighed eighty-five pounds when he was born, and he immediately started gaining weight. Weight gain is a sign of good health, but it is not so easy to measure. Imagine putting a calf on a scale and asking him to stand still!

Instead, farmers use an ingenious two-sided tape measure. There is a direct correlation between how big a calf measures around their body behind the front legs and how much they weigh.

The Nottermanns periodically measure all their calves to keep track of their growth. Here, Lima Bean measures thirty inches around his middle, which correlates to eighty-five pounds in weight.

When Lima Bean turns two weeks old, it’s time to teach him to drink his milk out of a bucket. Helm mixes up the milk in the same way he always has, but now he puts it into a bucket instead of a bottle.

The first time Nancy shows Lima Bean the bucket, he is a bit indignant. “That’s not a bottle!” But she puts her hand in the bucket and twiddles her fingers to encourage him to suck on her fingers in the milk. She hopes she can gradually slip her fingers out of the milk while his head stays in the bucket, continuing to drink. Instead, Lima Bean pops his head up right away, looks at her, and head-butts the bucket. It’s time to try again!

This time, Lima Bean puts his nose in the milk all the way up to his eyeballs, sucks all the milk down in about two seconds, and then beats up the pail trying to get more. Oscar, his buddy next door, is much more relaxed. He just puts the tip of his nose in the milk and slowly drinks it all with no drama.

Nancy, Helm, or Ben hides around the corner to keep an eye on the calves but not be seen while the calves are switching from bottle to bucket. It’s important not to distract them as they explore this new way of drinking. In addition to milk, all the calves have had buckets of water in their pens from the beginning. Some decide that water is a good thing and figure out how to drink from the bucket right away. Others, however, need to be taught. There is a big range of personalities!

During the first three months of life, Lima Bean and his buddies need the most care. The Nottermanns’ day starts at 6:30 in the morning with feedings and health checks. The calves have to be kept at a comfortable temperature. This means the windows in the calf barn are often opened or closed and calf jackets are put on or taken off. Evening chore time starts at 4:30 p.m. when the calves are fed again. Right before bed, Nancy goes to the barn for a last health check. Sometimes she has to give a calf extra fluids late at night.

The pens are mucked out every day. “Mucking out” is farmer talk for removing poop, or manure. The calves then get a clean layer of bedding straw, which the Nottermanns call “fresh sheets.” Lima Bean loves his fresh sheets and jumps all about when they arrive!

As you might imagine, a barn full of calves and manure has a distinctive odor that clings to clothes. To make sure that barn smells stay in the barn and do not enter the house where Nancy and Helm live, they keep important “house rules.”

Clothes worn in the barn do not enter the house. This includes pants, shirts, coveralls, and jackets. One side of the mudroom holds all the barn clothes. Before entering the house, everyone changes out of their barn clothes and back into house clothes.

All shoes and boots worn outside do not enter the house. A tray in the mudroom holds outdoor shoes. If someone needs to run into the house just to grab something and doesn’t want to change shoes, they put plastic bags over their shoes to keep dirt and manure from being tracked into the house. When the calves are young and need a lot of attention, people might change into and out of barn clothes and boots ten times a day!